-

Posts

7,962 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

18

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Gallery

Downloads

Blogs

Events

Store

Aircraft

Resources

Tutorials

Articles

Classifieds

Movies

Books

Community Map

Quizzes

Videos Directory

Everything posted by fly_tornado

-

Ethiopian 737-800 Max crash - No survivors

fly_tornado replied to kgwilson's topic in Aircraft Incidents and Accidents

The Wall Street Journal (subscription required) is reporting the return to service of the Boeing 737 MAX is being pushed back because something in the investigation has prompted a review of training in the previous model. There are more than 5,000 Boeing 737NG models in use all over the world and the safety record of the type is considered good. The news clearly annoyed Boeing. “While we are working with the FAA to review all procedures, the safety of the 737 NG is not in question,” a Boeing spokesman told the Journal’s Andy Pasztor. The spokesman also noted “its 20-plus years of service and 200 million flight hours.” Earlier this week, acting FAA Administrator Dan Elwell said the FAA was going to take its time with the MAX investigation and he wasn’t concerned if it took another year. The revisiting of procedures for a 20-year-old design was prompted by the fact that emergency training for the MAX was largely based on that from the NG. The NGs don’t have the MCAS system that is at the root of the investigation but the Journal says some of the MAX procedures are based on an assumption that pilots would know what to do (stabilizer trim cutoff switches) within seconds of the nose going down for no apparent reason. The Journal says the FAA is looking at whether the software fix for the MAX will give pilots more time, about 20 seconds, to react. Meanwhile, pilots unions have told Boeing to stop blaming the pilots for the two fatal crashes that prompted this ever-expanding investigation. The crews of Lion Air 610 and Ethiopian Airlines 302 fought a losing battle to try and overcome the persistent nose-down actions of the MCAS resulting in 346 deaths and top Boeing officials have said some of that’s on the pilots. "Shame on you ... we're going to call you out on it," Dennis Tajer, head of the Allied Pilots Association, which represents American Airlines pilots, told CNN. "That's a poisoned, diseased philosophy." -

the RAA can't go broke though, it can just keep bumping up fees

-

but still doing an amazing job

-

Ethiopian 737-800 Max crash - No survivors

fly_tornado replied to kgwilson's topic in Aircraft Incidents and Accidents

boeing are in a heap of legal trouble, some of the bigger airlines are going to be getting some free planes -

I tried finding tinted poly-carbonate in Brisbane and the thinnest stuff I could find was 3mm, which was too thick.

-

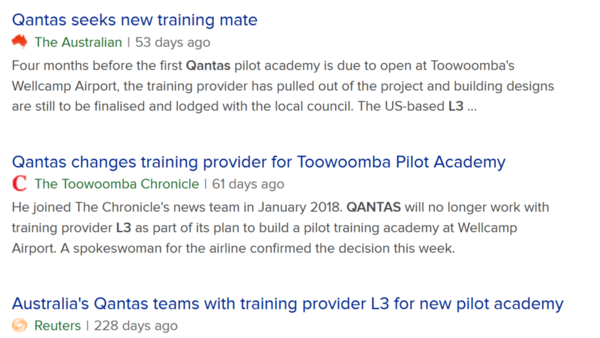

I subscribe to the local paper and most of these articles are behind the paywall, Wellcamp is a shining example of what happens when you bypass the normal planning procedures and do it because you can.

-

CASA set to crack down on spin training

fly_tornado replied to fly_tornado's topic in Trips/Events/Seats

i meant to put this video in the gov folder but missed -

Wellcamp Airport general manager resigns 'unexpectedly' WAGNER Corporation has launched a nationwide hunt for the next general manager of Wellcamp Airport after Sara Hales unexpectedly resigned this week. Mrs Hales, who worked her way up from community consultation to the leading role over the past five and a half years, has been thanked for work bringing the airport from conception to fruition. "Sara gave me her resignation earlier this week which was unexpected," Wagner Corporation chairman John Wagner said. "She is going to explore some other opportunities, including potentially working for herself. "She has been here for five-and-a-half years and has done a fantastic job in positioning the airport into a very well-run business and we're sad to see her go. "We appreciate everything she has done to get the airport to where it is." Mrs Hales said she was grateful to be part of the airport's development, describing her rise from community consultation to general manager as a "terrific ride". "I'm very proud of what we've achieved over the last five years," she said. "I really look forward to finding new ways to make a difference and continue to give back to Toowoomba and Queensland." She hoped to remain in the region. Mrs Hales is the second general manager at the airport since it opened in 2014. She replaced Phil Gregory in the top role in 2017. Mr Wagner said the position would oversee all operations at the airport, including export, with a nationwide recruitment search. The online job listing called for someone who understood regulatory environment of Australian airports, and experience in the "development of Australian Border Agency Service at new international airports is highly regarded". @mnewbery time to brush up on your interview techniques

-

-

its worth pointing out that labor raised the retirement age to 68, so its easy to see why they had such a collapse in their vote. everyone retires eventually

-

to be fair though the banking royal commission only got up because of a few key nationals, sadly he wasn't one of them

-

I just thought you would have known of an issue that he's been influential in as a shadow minister. All I can think of is reducing the craft beer excise. I just think he's a bit of a lightweight

-

name an issue Albanese has any influence over in the last 5 years? take your time

-

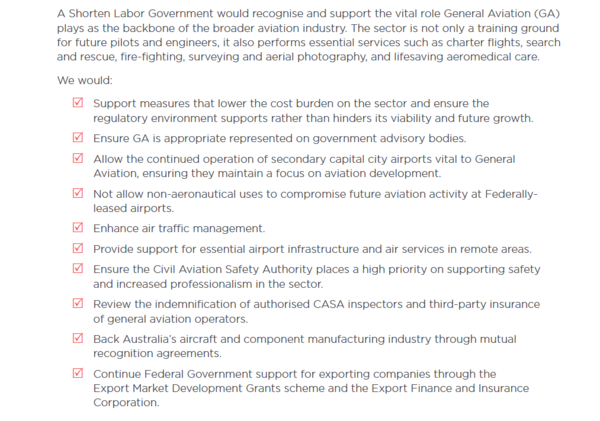

typical labor, broad goals that mean very little

-

probably not a consideration for most voters but its interesting to see that they are trying [/url]https://anthonyalbanese.com.au/albo_wpbird/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Aviation-Policy-FINAL.pdf

-

Ethiopian 737-800 Max crash - No survivors

fly_tornado replied to kgwilson's topic in Aircraft Incidents and Accidents

WASHINGTON—A simulator session flown by a U.S.-based Boeing 737 MAX crew that mimicked a key portion of the Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302 (ET302) accident sequence suggests that the Ethiopian crew faced a near-impossible task of getting their 737 MAX 8 back under control, and underscores the importance of pilots understanding severe runaway trim recovery procedures. Details of the session, shared with Aviation Week, were flown voluntarily as part of routine, recurrent training. Its purpose: practice recovering from a scenario in which the aircraft was out of trim and wanting to descend while flying at a high rate of speed. This is what the ET302 crew faced when it toggled cutout switches to de-power the MAX’s automatic stabilizer trim motor, disabling the maneuvering characteristics augmentation system (MCAS) that was erroneously trimming the horizontal stabilizer nose-down. In such a scenario, once the trim motor is de-powered, the pilots must use the hand-operated manual trim wheels to adjust the stabilizers. But they also must keep the aircraft from descending by pulling back on the control columns to deflect the elevator portions of the stabilizer upward. Aerodynamic forces from the nose-up elevator deflection make the entire stabilizer more difficult to move, and higher airspeed exacerbates the issue. The U.S. crew tested this by setting up a 737-Next Generation simulator at 10,000 ft., 250 kt. and 2 deg. nose up stabilizer trim. This is slightly higher altitude but otherwise similar to what the ET302 crew faced as it de-powered the trim motors 3 min. into the 6 min. flight, and about 1 min. after the first uncommanded MCAS input. Leading up to the scenario, the Ethiopian crew used column-mounted manual electric trim to counter some of the MCAS inputs, but did not get the aircraft back to level trim, as the 737 manual instructs before de-powering the stabilizer trim motor. The crew also did not reduce their unusually high speed. What the U.S. crew found was eye-opening. Keeping the aircraft level required significant aft-column pressure by the captain, and aerodynamic forces prevented the first officer from moving the trim wheel a full turn. They resorted to a little-known procedure to regain control. The crew repeatedly executed a three-step process known as the roller coaster. First, let the aircraft’s nose drop, removing elevator nose-down force. Second, crank the trim wheel, inputting nose-up stabilizer, as the aircraft descends. Third, pull back on the yokes to raise the nose and slow the descent. The excessive descent rates during the first two steps meant the crew got as low as 2,000 ft. during the recovery. The Ethiopian Ministry of Transport preliminary report on the Mar. 10 ET302 accident suggests the crew attempted to use manual trim after de-powering the stabilizer motors, but determined it “was not working,” the report said. A constant trust setting at 94% N1 meant ET302’s airspeed increased to the 737 MAX’s maximum (Vmo), 340 kt., soon after the stabilizer trim motors were cut off, and did not drop below that level for the remainder of the flight. The pilots, struggling to keep the aircraft from descending, also maintained steady to strong aft control-column inputs from the time MCAS first fired through the end of the flight. The U.S. crew’s session and a video posted recently by YouTube’s Mentour Pilot that shows a similar scenario inside a simulator suggest that the resulting forces on ET302’s stabilizer would have made it nearly impossible to move by hand. Neither the current 737 flight manual nor any MCAS-related guidance issued by Boeing in the wake of the October 2018 crash of Lion Air Flight 610 (JT610), when MCAS first came to light for most pilots, discuss the roller-coaster procedure for recovering from severe out-of-trim conditions. The 737 manual explains that “effort required to manually rotate the stabilizer trim wheels may be higher under certain flight conditions,” but does not provide details. The pilot who shared the scenario said he learned the roller coaster procedure from excerpts of a 737-200 manual posted in an online pilot forum in the wake of the MAX accidents. It is not taught at his airline. Boeing’s assumption was that erroneous stabilizer nose-down inputs by MCAS, such as those experienced by both the JT610 and ET302 crews, would be diagnosed as runaway stabilizer. The checklist to counter runaway stabilizer includes using the cutout switches to de-power the stabilizer trim motor. The ET302 crew followed this, but not until the aircraft was severely out of trim following the MCAS inputs triggered by faulty angle-of-attack (AOA) data that told the system the aircraft’s nose was too high. Unable to move the stabilizer manually, the ET302 crew moved the cutout switches to power the stabilizer trim motors—something the runaway stabilizer checklist states should not be done. While this enabled their column-mounted electric trim input switches, it also re-activated MCAS, which again received the faulty AOA data and trimmed the stabilizer nose down, leading to a fatal dive. The simulator session underscored the importance of reacting quickly to uncommanded stabilizer movements and avoiding a severe out-of-trim condition, one of the pilots involved said. “I don’t think the situation would be survivable at 350 kt. and below 5,000 ft,” this pilot noted. The ET302 crew climbed through 5,000 ft. shortly after de-powering the trim motors, and got to about 8,000 ft.—the same amount of altitude the U.S. crew used up during the roller-coaster maneuvers—before the final dive. A second pilot not involved in the session but who reviewed the scenario’s details said it highlighted several training opportunities. “This is the sort of simulator experience airline crews need to gain an understanding of how runaway trim can make the aircraft very difficult to control, and how important it is to rehearse use of manual trim inputs,” this pilot said. While Boeing’s runaway stabilizer checklist does not specify it, the second pilot recommended a maximum thrust of 75% N1 and a 4 deg. nose-up pitch to keep airspeed under control. Boeing is developing modifications to MCAS, as well as additional training. Simulator sessions are expected to be integrated into recurrent training, and may be required by some regulators, and opted for by some airlines, before pilots are cleared to fly MAXs again. The MAX fleet has been grounded since mid-March, a direct result of the two accidents. [/url]https://aviationweek.com/commercial-aviation/ethiopian-max-crash-simulator-scenario-stuns-pilots?NL=AW-05&Issue=AW-05_20190513_AW-05_525&sfvc4enews=42&cl=article_1&utm_rid=CPEN1000001417826&utm_campaign=19626&utm_medium=email&elq2=6dd9eec1bd614228a83b544a96f1e97d -

they aren't going broke, they just aren't making mega bucks

-

Most of the wagner's news is behind the paywall, I'm just posting articles here to keep folks up to date, I'm not forcing you to read this. wow share price dropped to $1.70 today, there must be something up for people to be shorting them like this

-

Can't turn, Can't climb, Can't run: F35 problems

fly_tornado replied to fly_tornado's topic in Military Aviation

Tokyo (CNN)Wreckage from a Japanese F-35 stealth fighter that crashed into the Pacific almost a month ago has been recovered, Japan's defense minister said Tuesday, but the reason for the loss of one of the world's most advanced warplanes remains a mystery. Pieces of the jet's flight recorder and cockpit canopy have been lifted from the ocean floor, Defense Minister Takeshi Iwaya told reporters in Tokyo. He described the condition of the flight recorder as "terrible" and said the device's memory part was missing, leaving investigators still wondering how the US-designed jet crashed April 9. The jet and its pilot, Maj. Akinori Hosomi, went missing while on a training mission from Misawa Air Base in northern Japan. Hosomi, a 41-year-old with 3,200 hours of flight experience, was last heard from when he signaled to his squadron mates that he would have to abort the mission before his craft disappeared from radar. alt=A%20Japan%20Coast%20Guard's%20vessel%20and%20US%20military%20plane%20search%20for%20a%20Japanese%20fighter%20jet,%20in%20the%20waters%20off%20Aomori,%20northern%20Japan,%20Wednesday,%20April%2010,%202019.https://cdn.cnn.com/cnnnext/dam/assets/190410005054-file-f-35-01-exlarge-169.jpg[/img] A Japan Coast Guard's vessel and US military plane search for a Japanese fighter jet, in the waters off Aomori, northern Japan, Wednesday, April 10, 2019. Pieces of the plane's tail fins were recovered from the sea shortly thereafter, but noting else turned up until May 3, when the US Navy-chartered deep-sea diving support vessel Van Gogh collected a part of the flight recorder, Iwaya said Tuesday. The US-chartered ship was acting on information gleaned by Japan's deep sea research ship Kaimei, which carries a remotely operated submarine and equipment to grab samples from the seabed. Japan's Defense Ministry did not reveal exactly where or at what depth the latest pieces were found. The plane was east of Misawa Air Base over the Pacific when it disappeared. The Defense Ministry said the search for more wreckage would continue and includes a Japanese destroyer as well as chartered commercial salvage ships. alt=A%20Japanese%20F-35A%20arrives%20at%20Misawa%20Air%20Base%20in%20northern%20Japan%20in%202018.https://cdn.cnn.com/cnnnext/dam/assets/181014092846-japan-f-35-misawa-exlarge-169.jpg[/img] A Japanese F-35A arrives at Misawa Air Base in northern Japan in 2018. Japan grounded the other 12 active F-35s in its fleet after the crash. They remain out of action while the investigation continues, the Defense Ministry said. With 147 of the $100-million-plus F-35s on order, Japan intends the planes to be the mainstay of its air forces for decades to come, and officials have said since the crash that their faith in the program has not wavered. The jet that crashed was the first off a Japanese assembly line for the F-35A, one of three variants of the plane. Japan had announced plans before the crash to stop production there in 2022 and import the rest of its fleet from the US. The United States has hundreds of the jets in its fleets and on order, as do a dozen other countries. Those jets continue in operation. US Air Force F-35As, the same type as the Japanese jet that crashed, have since flown combat missions in the Middle East. -

Sukhoi Superjet 100 Crash

fly_tornado replied to willedoo's topic in Aircraft Incidents and Accidents

I only saw this video, I assume that its been cut a fair bit https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A0TH0iocVE4 -

Wagners makes changes to new hangars at Wellcamp Airport THE Toowoomba Regional Council has approved changes to an original plan to expand Wellcamp Airport by owner the Wagner Corporation. The application for a change to the existing approval from 2014 was submitted late last year, and involved building two hangars at the site. Precinct Urban Planning's Jess Garratt explained that the change revolved around building a new hangar while converting an existing warehouse into a second one. "Both buildings will be located to the south-east of the existing airport terminal as illustrated on the proposed development plans attached," she wrote. TRC planning officer Geoff Broadbent agreed that the proposal was a minor change, and approved it. The change also included several alterations to the conditions, including the car parking requirements, easements and landscaping. What are they doing for a warehouse?

-

Sukhoi Superjet 100 Crash

fly_tornado replied to willedoo's topic in Aircraft Incidents and Accidents

it was properly on fire by the time they landed